What Is The Future Of Sex?

What is sex for?

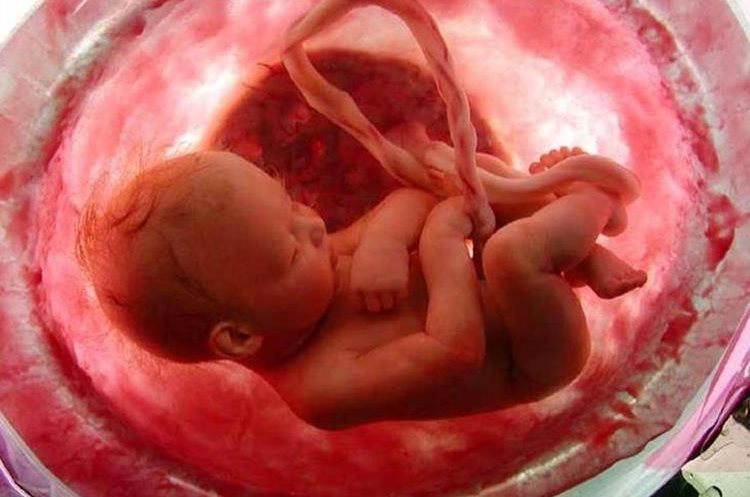

From a biological point of view, there is an apparent reason for sex between human beings. We have sex because it satisfies our biological urges, including the urges needed to procreate and bond. The biblical book Song of Songs of Solomon celebrates passionate, erotic, and wild sex on its terms, between two lovers – not between husband and wife, as Christians later misinterpreted the poem.

Another vital reason for sex comes from Aristotle. In the work, First Analytics of the 4th century BC, the Greek philosopher presents the following syllogism: “Being loved, then, is preferable to sexual intercourse, according to the nature of erotic desire. Erotic desire, then, is more a desire for love than for sexual relations. If that’s what it’s all about, that’s its end. Either sexual intercourse, then, is not an end at all or is for the sake of being loved.” For Aristotle, “love is the purpose of erotic desire.” “It is not love that has sex as its objective. It is sex that has love as its objective”. The real reason we have sex, according to Aristotle, is not because we want to have sex but because we want to love and be loved. Sex is about something higher, something nobler. Sex is not the ultimate goal of erotic desire. If Aristotle is correct, sex has no erotic purpose – its true purpose lies elsewhere. In short, we don’t have sex for sex’s sake. Why do we have sex then? To procreate, for sure. To connect, too. But these are just two of many possible answers. Like many cultural phenomena, sex goes beyond its why. Maybe it’s time to admit that pleasure is the main reason most of us – including the most religious of us – have sex.

Homosexual behavior is quite common in the animal kingdom. The Japanese macaque, the fruit fly, the brown beetle, the Laysan albatross, and the bottlenose dolphin – are just some of the more than 500 species that develop homosexual relationships. In a world where same-sex sexual activity is widely accepted as a natural and healthy variation of human sexuality, it is no longer necessary to form a public identity based on sexual practices. Perhaps the more we separate sex from its purpose, the fewer people will think about what the sexual act can mean and how it can contribute to an individual’s identity. Like many children, I was taught to judge sexual ethics from a single perspective – whether sexual intercourse had taken place within a committed, monogamous relationship (usually marriage). But eventually, I began to question this pattern – mainly because the same people who taught me this also taught me that human beings were created by God a few thousand years ago. Most heterosexual sexual acts do not result in the birth of a baby, and for some reason, sex without procreation is never classified as unnatural in the way that homosexual sex without procreation is often condemned.